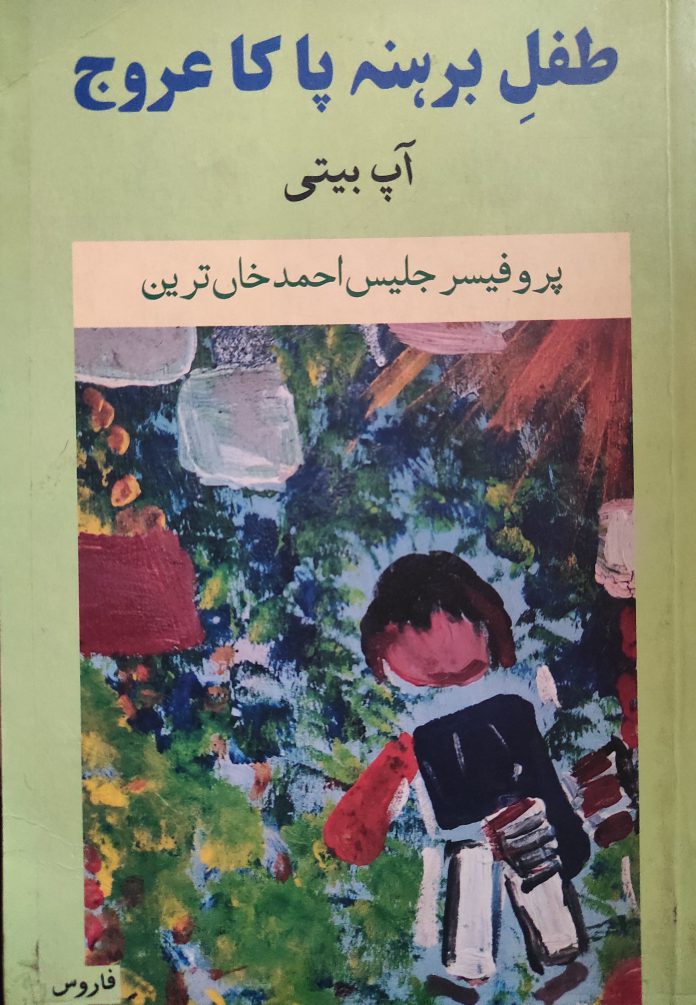

(Rise of a Barefoot Boy: An Autobiography)

By: Mushtaq Ul Haq Ahmad Sikander

Prof. Jalees Ahmad Khan Tareen’s “Rise of a Barefoot Boy—An Autobiography,” translated into Urdu by Mahmood Faizabadi, is both a self-portrait and a meditation on identity, resilience, and reform in modern India. Framed by Sudheendra Kulkarni’s thoughtful foreword, Tareen’s memoirs speak as much to the heart of a reader as to the intellect, moving beyond conventional life stories into the realm of social commentary. The Urdu translation breathes local life into a tale that is at once personal and profoundly emblematic of the Indian Muslim experience in the late twentieth century.

From the outset, Tareen places his generation within a turbulent historical context, describing it—accurately—as the bridge between the decades spanning 1940–1980, eras marked by shifts in weltanschauung, or worldviews, and social orders. That sweeping statement is not only an introduction to his life, but also an invitation to read each episode as both particular and paradigmatic. He crafts a narrative in which childhood deprivation and the absence of privilege redefine character, ambition, and ultimately achievement. Orphaned at the age of seven and growing up barefoot, he describes a world deprived not only of electricity but also, at times, of hope. The absence of his father—whose death left a family vulnerable and searching for solace—never became grounds for resignation. Instead, it set the stage for a shared tenacity within his joint family. The texture of those memories, relayed with gentle nostalgia, reveals a childhood dominated by domestic chores, homeschooling, and solidarity among siblings. It is this understated togetherness, illuminated by the “dim glow of kerosene lamps,” that forms the bedrock of Tareen’s character and career.

Immediately, one is struck by the authenticity of his recollections about post-independence rural life—a world that is often idealized but rarely relived so candidly. He describes how the joint family adapted to tragedy, how the bonds with relatives shielded and nurtured him in those formative years, and how everyday life flourished despite the lack of material comforts. This is not a narrative of victimhood, but of survival and dignity, echoing those collective memories that so many in South Asia quietly hold. The autobiography is replete with such vignettes, transforming it from a simple recollection into a sociological document.

The academic odyssey that followed was no less significant. When Tareen entered university, ambition met adversity. The drama is evident in his reflections on peer rivalries and the bureaucratic culture, where sycophants clustered near the Head of Department, seeking favor and creating mistrust (P-161). The academic realm, allegedly governed by merit, reveals itself to be beset by hierarchy, sectarianism, and politics—a microcosm of larger societal malaise. His narrative of professional hurdles, especially attempts to block his elevation to the post of Professor, is recounted with both candor and restraint. Liberal and non-communal non-Muslims, rather than co-religionists, often emerged as allies, helping to lift him above the machinations of narrow-minded rivals. Here, Tareen is explicit in his gratitude for the social and intellectual capital offered by those who transcended communal identities, an observation that underscores the non-monolithic nature of Indian academia.

The story’s tone is further sharpened by Tareen’s experience with discrimination on religious grounds, particularly when the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) labeled him “communal.” This charge, leveled in an atmosphere fraught with politics and suspicion, failed to shake his secular convictions or to tarnish his reputation, as his later achievements readily attest. The persistent challenges from both institutional politics and external perceptions did not deter him; his eventual rise affirms the old dictum that “character is destiny.”

The memoir’s most dramatic chapters unfold during his tenure as Vice Chancellor of Kashmir University. Tareen arrives at a university beset by corruption and nepotism, and his honest administrative interventions expose more than simply inefficiency—they bring to the surface latent opposition and menace. The narrative is given urgency when, following administrative reforms, the Kashmir University Teachers Association (KUTA) mobilizes resistance, supported by a threat letter from a militant organization. It is a chilling reminder of the volatility of public life in Kashmir and of the courage demanded by real reform. There is no grand farewell for Tareen when his term ends, and this absence itself is significant—institutions rarely honor those who expose their flaws. Instead, a more lasting tribute is found in the university’s transformation: its A+ NAAC accreditation, its hosting of the Prime Minister and other dignitaries, and its successful convocation ceremonies.

Tareen’s memoir, “Fire Under Snowflakes: The Return of K.U,” provides a unique lens on Kashmir’s malaise, but this autobiography goes further, dissecting the divisions between Pandits and Muslims, as well as the damaging role played by political actors such as Governor Jagmohan. Tareen insists, however, that youth, particularly in Kashmir, retain a non-communal temperament—a note of hope in an otherwise fraught landscape.

In subsequent sections, especially recounting his term as Vice Chancellor of Pondicherry University, Tareen describes a familiar pattern: entrenched lobbies, character assassination, and calculated misinformation directed at ministries and the Prime Minister’s Office. Each episode becomes a case study in persistence, as the author refuses to yield to either political pressure or institutional inertia.

A recurring motif in Tareen’s reflections is the dilemma of Indian Muslims. On (P-230), he offers a bold diagnosis: the perceived decadence and underdevelopment of the community stem not from external antagonism alone, but significantly from low self-confidence and a lack of self-reliance. This observation is, in literary terms, both a confession and an admonition—it moves away from polemic and towards honest, if uncomfortable, introspection. His prescription carries ethical weight: say no to dowry, which reduces families to penury, and embrace internal reform as the only path from stagnation to renewal.

There is an admirable ethical rigor in his philosophy regarding public office. The book repeatedly advocates for integrity and responsibility. Tareen’s refrain is clear: use work and position for institutional good, not for personal gain. Those who hoard illicit money sacrifice inner peace, and their achievements remain hollow—the type of moral argument increasingly rare in contemporary autobiographical accounts.

Tareen’s views on education—particularly of girls—are pressing and prophetic. He laments the lack of Muslim contribution to the broader societal and intellectual landscape, insisting that without prioritizing girl education, the community will neither progress nor participate meaningfully in the nation’s future. The chapter is marked by urgency and vision, supporting the argument that empowerment is as much a product of personal resolve as it is of policy.

His critique of madrasa graduates is equally pointed. He suggests that products of religious seminaries often remain trapped in insular poverty, unable to build bridges with non-Muslims or to thrive in secular domains. This isolation, compounded by external suspicion and internal inertia, is the principal challenge faced by the community. Tareen rejects the notion that terrorism tags and communal taunts are immutable; on the contrary, he believes they can be dissolved through the cultivation of genuine, interfaith relationships.

Conspicuously absent from the memoir is the customary love story or romantic diversion that so often populates autobiographical writing. Tareen’s life has been devoted not to emotional indulgence, but to a larger mission of reform, learning, and service. The emotional austerity of the narrative, skillfully preserved in Faizabadi’s translation, may render it “dry” by conventional standards but is, in context, both necessary and admirable.

Throughout, “Rise of a Barefoot Boy—An Autobiography” challenges, inspires, and instructs. Its pages are animated by memories of kinship, sacrifice, and self-discovery. The Urdu translation itself is a literary accomplishment, capturing not only the intelligence and candor of the original but also its cultural texture—a rare feat in contemporary biographical literature. Sudheendra Kulkarni’s foreword is entirely justified in its recommendation that this book be read not only by students and academics but by anyone interested in the moral and intellectual journey of modern India.

As the final pages close, the reader is left with the impression of an individual who did not evade adversity, but transmuted it; who did not succumb to discrimination, but rose above it; and who, in choosing service over self-interest, crafted a legacy whose significance far exceeds the boundaries of personal narrative. “Rise of a Barefoot Boy—An Autobiography” thus stands as an exemplar of literary autobiography, its strength anchored in the authenticity of experience and its wisdom offered freely to the reader, as all good books must.

(M. H. A. Sikander is Writer-Activist based in Srinagar, Kashmir and can be reached at [email protected])