By: Mushtaq Ul Haq Ahmad Sikander

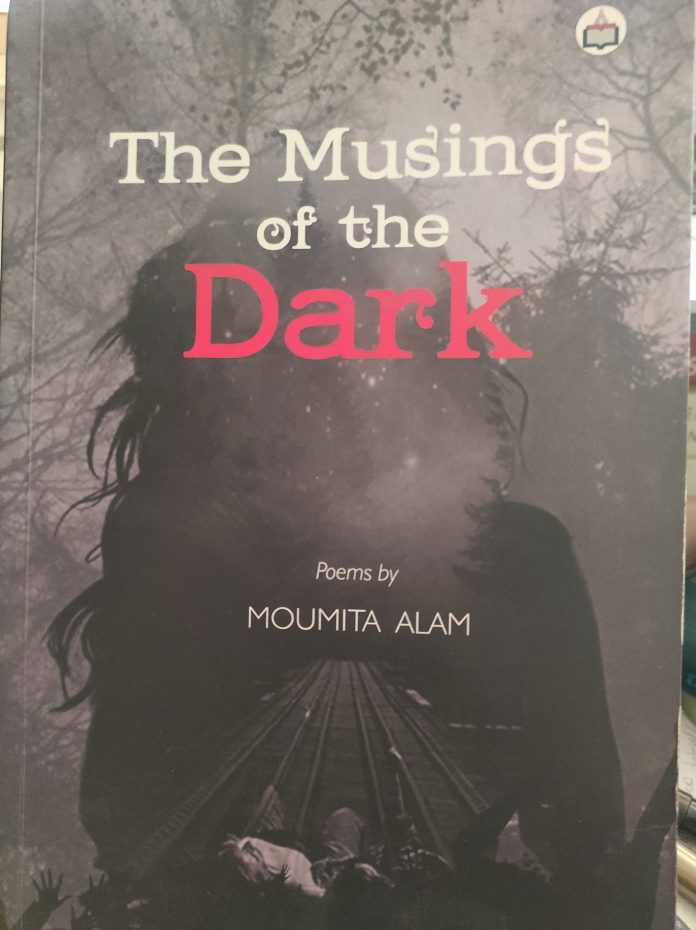

Moumita Alam’s The Musings of the Dark is one of the most compelling and ethically resonant poetic debuts in contemporary Indian literature. Within its pages, Alam gives voice to a conscience that refuses complacency. Her poems emerge as meditations from within the turbulence of our time—an age marred by authoritarianism, gender violence, and moral corrosion—yet they ring with clarity, conviction, and lyrical restraint. The book arrives at the crossroads of grief and resistance, and with astonishing assurance transforms both into a moral aesthetic.

Krishnendu Das, in his perceptive introduction, defines poetry as “emotional, rational, intense, subjective, subdued, objective, rhythmic at the same time.” These seemingly contradictory qualities find a rare balance in Alam’s voice. Her language is lucid yet layered; her sensibility both fiercely political and deeply human. Das is right to note that “She writes with such deft hand and she handles the themes of universal crisis with so much dexterity that it is hard to believe that this is her first published work.” There is nothing tentative about these poems. They bear the maturity of a poet who knows that in times of crisis, silence becomes complicity, and words, however fragile, must take on the burden of truth.

Alam’s poetry belongs unmistakably to what may be called the poetics of witness. It is neither escapist lyricism nor detached observation. Rather, her poems confront the spectacle of violence with unyielding candour. The haunting lines—“How the voices are coming / With weeping noises / And shattered images / After the throat has long been slit” (p.20)—testify to a world where brutality has become quotidian. The poem’s fragmented imagery—“weeping noises,” “shattered images”—recalls both the cacophony of media spectacles and the silent aftermath of grief. It is a poetry that listens, not merely to words, but to wounds.

Her political consciousness is explicit and courageous. The poem declaring, “Don’t let the bloody fascists dictate / Our hearts / Let’s prove them / Land they can rule not our hearts” (p.22), speaks from the frontlines of emotional and ethical defiance. The insistent repetition of “hearts” suggests that amid political dispossession, the ultimate site of freedom remains interior. The subsequent affirmation—“They don’t know / We have won the battle long ago / Boots don’t rule our hearts / Freedom births every day in courtyards” (p.27)—extends this defiance into a historical continuum of resistance. The imagery of “boots” against “courtyards” juxtaposes militarized authority and domestic resilience, suggesting that rebellion begins within the intimate moral geographies of everyday life.

What distinguishes Alam’s political engagement is that it is guided by conscience, not ideology. In a remarkable redefinition of prayer, she writes

“The prayer is not for the Sinners

The prayer is not for theBelivers

The prayer is for the conscience,

The conscience that bleeds everyday

The conscience that dies everyday

The conscience that cries without words

The conscience that will bring justice someday.” (p.31)

Here the poet transposes the sacred from the heavens to the human. “Conscience” becomes the living arbiter of justice, bleeding and dying like any mortal being. Yet even in its affliction lies redemption. The poem’s diction, unembellished and rhythmic, recalls the cadences of a collective lament. By removing religious and moral binaries—“sinners” and “believers”—Alam situates the moral struggle within humanity itself.

This inward ethical struggle runs parallel to her outward political critique. When she observes, “All the cities of mine are smelling warm gun powders / The siren of the khakis, and that killing shout / All are the same” (p.50), her imagery maps violence onto urban consciousness. Her “cities” stand for the moral disintegration of national life—each city interchangeable in its complicity and fear. The sensory immediacy of “smelling warm gun powders” transforms memory into physical sensation. It is this visceral language that makes her witness believable: she names what others have normalized.

Alam’s poems do not spare power, but neither do they romanticize victimhood. At one point, she questions her own medium with an almost Socratic humility: “Poetry / How do you / Record so minutely / The bloody hands / Of the rulers!” (p.60). This interrogation turns the act of writing into an ethical dilemma. Can poetry, she seems to ask, adequately document the enormity of human cruelty without violating its sanctity? In posing this question, she aligns herself with the revisionist tradition of conscience poetry, where moral responsibility and artistic humility coalesce.

Many of Alam’s verses derive their strength from the vividness of lived experience. The line “Do you not know / I have grave in my home / And home does not lessen my hunger, Sahab” (p.71) evokes layered metaphors of deprivation. The “grave” within the “home” collapses domesticity into decay, suggesting that ordinary existence itself has become a burial ground for aspiration and dignity. The address “Sahab” implicates both class and gender hierarchies, reminding the reader that hunger—physical or moral—is structured by inequality.

Equally powerful is her portrayal of bureaucratic neglect. In a devastating image, she writes: “He will be found by / Roadside still wearing the mask on his face / Given by some holy men / The mask is the only thing intact / In his otherwise rotten body / His existence will be acknowledged / When it will be stinking to / The babus.” (p.86). The “mask,” initially a symbol of safety and piety, becomes the final remnant of humanity, intact amid bodily decomposition. The state, represented by “babus,” recognizes the dead only when they become an administrative inconvenience. This is not realism alone—it is ethical allegory distilled into verse.

If Alam’s poems of political grief and civic anguish are striking, her feminist utterances are incandescent. She writes about the desecrated female body without euphemism, refusing the decorum that has historically silenced women poets. Her visceral lines—“Here the baby of three years can’t escape / The lust of an uncontrollable penis / Here women are born to serve the / Bastard males for lives in the / Sanctimonious bond of marriage. / Here wives are nothing more than vaginas / And husbands are their masters.” (p.118)—shock with their unfiltered candour. This is not vulgarity; it is brutal truth phrased with literary precision. By beginning each stanza with “Here,” the poet situates the horror within the immediacy of the present, dismantling the reader’s illusion of detached safety.

Her declaration continues with equal fire:

“Don’t tear apart the hymens to satisfy only

Your male ego that rejects to believe

The thing called female orgasm

You are not a king, boy

And my bed is not your kingdom

To rule as a frustrated ruler

Destroying everything on his way.” (p.126)

These lines constitute one of the most direct feminist articulations in recent Indian poetry. Alam overturns familiar hierarchies, deconstructing the patriarchal metaphor of kingship. The “bed,” long used in literature as a site of submission, becomes in her verse a battlefield for autonomy. The tone combines accusation and emancipation, anaphoric rhythm and lucid argument. As in her political poems, she exposes domination—here sexual rather than ideological—as a manifestation of power and ego.

Despite the ferocity of her themes, Alam’s voice remains tempered by empathy. She juxtaposes societal cruelty with the quiet sorrows of modern estrangement: “When the old parents are gasping for / Lives and their sons sitting on their dreams / Are saying hello in video calls” (p.107). The deceptively simple lines mark a transition from collective violence to personal alienation. Technology, in her depiction, becomes a metaphor for emotional distance, and “video calls” symbolize the virtualization of intimacy in an age that simultaneously celebrates and erodes human connection.

Stylistically, The Musings of the Dark reveals a poet of conscious discipline. Alam writes in free verse, but her rhythm is measured and her imagery deliberate. She avoids ornate vocabulary, choosing a diction that mirrors everyday speech while carrying philosophical weight. The sparseness of punctuation accelerates the reading experience, creating the impression of breathless urgency. Her technique reconciles reflection with immediacy—a structure in which poems appear spontaneous yet are architecturally precise.

The imagery of the collection is tactile and sensory: gunpowder, throat, mask, womb, blood—objects that engage sight, smell, and touch, forcing readers to inhabit the reality she describes. At the same time, repetition in her line endings functions as moral insistence, turning poems into oral testimony. By alternating between colloquial registers (“Sahab”) and lyrical cadence, she situates her diction in a living Indian English continuum, grounded in reality but unconstrained by linguistic coloniality.

Yet Alam is never content with despair alone. Amid the shadows glimmers an unyielding faith in renewal. “Let us believe that / This time too will pass / Like all the tyrants have been killed / And men have found their lands time and again” (p.40) encapsulates this equilibrium between disillusion and endurance. The historical sweep of these lines acknowledges human cruelty as cyclical, yet insists on redemption as inevitable. This optimism, though subdued, prevents her poetry from devolving into nihilism. It is the optimism of those who believe that to articulate suffering is itself to resist it.

What ultimately distinguishes The Musings of the Dark is the merging of the aesthetic and the ethical. Alam’s poems are not mere reflections on injustice but living embodiments of dissent. They recall the spirit of poets like Faiz Ahmad Faiz, yet her tone remains uniquely her own—neither rhetorical nor academic, but intimate in its authenticity. Her refusal to detach art from ethics restores poetry’s historic vocation as the conscience of civilization.

Reading this collection, one becomes aware that Alam writes from within the fire rather than at a safe distance from it. Her poems inhabit the borderlands between personal pain and collective trauma, between lamentation and resistance. The musings of her darkness are not the murmurings of defeat but the meditations of a moral witness. Each poem is a fragment of conscience struggling for articulation, a cry distilled into language.

It is indeed remarkable that this is her debut work. The maturity of vision, the political sharpness, and the emotional lucidity confirm that a formidable new voice has entered Indian English poetry—one that writes not to ornament experience but to wrestle with it. The Musings of the Dark affirms that poetry, when freed from pretension, still possesses the power to console, confront, and transform.

Alam’s concluding conviction that “Freedom births every day in courtyards” (p.27) stands as the book’s final benediction. In a world haunted by fear, her poems reclaim the courtyard as a space of daily resurrection, where hope renews itself against the odds. Her work thus not only memorializes her era of anxiety but transcends it, offering readers a voice that fuses compassion with courage.

The Musings of the Dark is not merely a collection—it is a testament. It reminds us that amid collapsing certainties, poetry remains the last sanctuary of the human conscience. In Moumita Alam’s hands, that conscience speaks, bleeds, and dreams for justice—undaunted, unbroken, and luminously alive.

(Mushtaq Ul Haq Ahmad Sikander is Writer-Activist based in Srinagar, Kashmir & can be reached at [email protected])