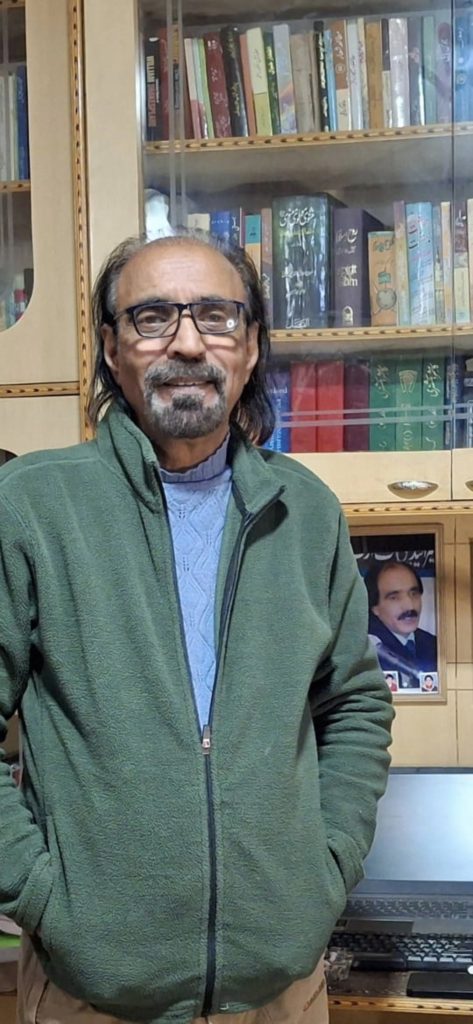

Few weeks back, I had the privilege of calling upon Prof. Shafaq Sopori, at his residence in Gogo, Humhama, Srinagar. We sat in a quiet room with books, notations, and manuscripts all around. Dr. Sopori welcomed me like an old friend. What followed was not just a conversation but a pilgrimage into the life and mind of a scholar who has lived many lives: as a poet, academic, fiction writer, musicologist, critic, and above all, a seeker.

Born in apple-rich Sopore, north Kashmir, Prof. Shafaq Sopori ‘Shafaq’ to the literary world, started his early career in the Department of Higher Education, Jammu and Kashmir, from where he rose to the rank of Professor before retiring from Cluster University, Srinagar. But retirement is hardly the right word for someone whose mind is ablaze with ideas, metaphors, and melodies.

His most distinctive academic achievement? A six-year sabbatical to immerse himself in Hindustani classical music, culminating in a groundbreaking PhD thesis titled Elements of Indian Music in Urdu Poetry. The thesis made him the first Indian scholar to bridge the poetic tradition of Urdu with the structured complexity of Indian classical music. “Music isn’t separate from language,” he told me, gesturing toward a raga notation framed on his wall. “It’s a deeper form of speaking. You just need to listen differently.”

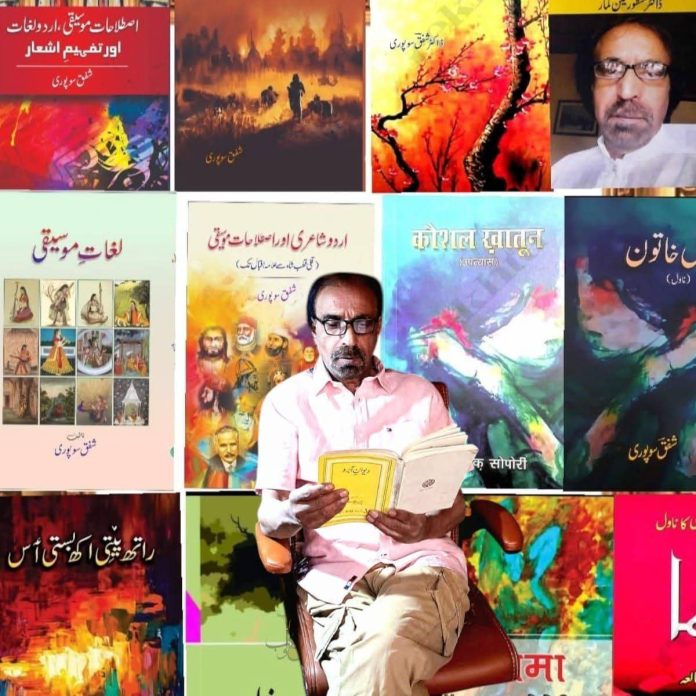

This deep listening produced an impressive corpus of musicological literature: Urdu Ghazal aur Hindustani Mausiqi, Farhang-e-Mausiqi, Mausiqi, Shairi aur Lisaniyat, and Glossary of Musical Terminology, among others. These are not just academic treatises but poetic bridges, where the pulse of a tabla meets the cadence of a couplet.

Dr. Sopori’s exploration didn’t stop at music. As a literary critic, he has revisited the works of the greats, Mir, Iqbal, Faiz, Hasrat Mohani, Wali Dakhni, Sauda, with an eye both loving and interrogative. His critical works like Jahat, Kalam-e-Faiz ka Arozi Mutala, and Lafz, Arooz aur Shairi offer rare insights into the poetics of sound and rhythm, prosody, a subject many avoid for its complexity, which he handles with ease and elegance.

His poetic endeavor includes titles like Dil-e-Khakbasar, Dasht Mein Door Kahin, Raisham Sarab Khwab, and most recently Pehli Tanhaiyan. Each poem brims with a classical clarity, but there’s an undercurrent of contemporary ache. “Pehli tanhaiyan woh hoti hain jo rooh ke andar bajti rehti hain,” he told me. The first loneliness is the one that keeps echoing within your soul.

A poet of deep social sensitivity and lyrical finesse, Shafaq Sopori writes in ghazals and nazm genre besides others. His poetry addresses a wide spectrum of themes from human suffering and spiritual yearning to social injustice and existential reflection all delivered in a tone that is bold, introspective, and unwaveringly humane. His verse resonates with a fearless moral vision, making him one of the compelling poetic voices of our times.

In the poetry of Shafaq Sopori, the delicacy of classical poetry and the charm of modern expression are present side by side. He has adorned traditional poetic forms like ghazal and nazm with contemporary themes.

His poetry is not only an interpretation of inner feelings, but also a mirror of social and psychological realities. The experiences of life, the suffering of the times and the personal agonies which he has endured, all are such that in his poetry they appear in this way as if these incidents have occurred with the reader himself.

These inward echoes have spilled into fiction too. Surprisingly, a space he only began exploring in 2016. But in less than a decade, he has written a shelf-full of novels. His debut, Neelma, is the first Urdu novel centered on India’s tribal (Adivasi) communities. Then came Firing Range Kashmir 1990, Qalandar Khan, Dariya Hai Chashm-e-Giryanak, and others—each mapping a different terrain of political, cultural, or emotional upheaval.

His other novels, including Mosa, Kaushal Khatun, Gulmohar ki Surkh Chidya, and his short story collection Raga Ragini aur Virjat Sour, continue to explore the themes of marginalization, memory, and music.

Beyond all this, he has served in a senior role at the J&K Academy of Art, Culture & Languages, where he compiled indexes of the Shirazah magazine. He has been widely honoured for his contributions, and his work has inspired M.Phil and Ph.D. dissertations across universities in Delhi, Jammu, and Hyderabad.

But accolades seem to sit lightly on his shoulders. What remains most moving is his humility, his deep engagement with both form and feeling, and his belief that art must serve as both memory and medicine.

Prof Shafaq admits that Kashmir has got the talent especially among youngsters but he wants them to work hard and not waste their time in what he terms as trivial events.

As I left his residence and stepped back into the bustling lanes of Srinagar, I carried with me not just notes from an interview, but a melody of meanings. One that kept playing long after the conversation had ended.

(A columnist, critic and academic Showkat shafi can be contacted at [email protected])