(The Gorakhpur Hospital Tragedy: A Doctor’s Memoir of a Deadly Medical Tragedy)

By: Mushtaq Ul Haq Ahmad Sikander

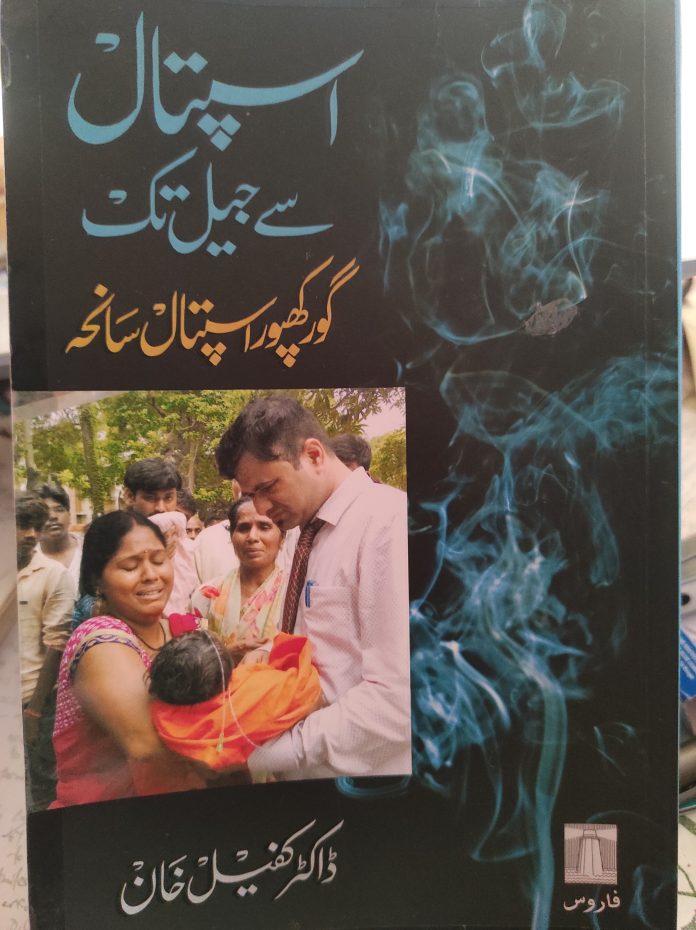

In the annals of contemporary India, few tragedies have exposed the moral hollowness of bureaucratic systems as starkly as the Gorakhpur hospital deaths of August 2017. In Aspataal Se Jail Tak—first published in English and now sensitively translated into Urdu—Dr Kafeel Khan revisits those suffocating days when infants died gasping for oxygen and truth itself was throttled in the corridors of power. The book is not only a personal memoir but also a political document: an indictment of apathy, arrogance, and systemic rot concealed behind the polished surfaces of official denial.

The Night of August 10, 2017

The narrative begins on the night of 10 August 2017, when BRD Medical College and Hospital in Gorakhpur suddenly ran out of liquid oxygen. For months, dues worth ₹68 lakh remained unpaid to Pushpa Sales—the hospital’s regular oxygen supplier. Despite repeated warnings about the imminent crisis, the administration delayed, evaded, and ignored. Dr Khan, a pediatrician on duty, describes how he spent the night frantically arranging oxygen cylinders from private sources, coordinating with the SSB to transport them, pleading with attendants, and appealing to suppliers who had every reason to refuse.

His efforts met indifference and obstruction at every turn. The Head of Department, Dr Mahima, was conveniently on leave, citing swine flu. The acting principal, Dr Jaiswal, remained unreachable at his private clinic. The district magistrate dismissed panic calls as “rumours,” claiming there was no dearth of oxygen. Even an oxygen plant owner refused to help out of resentment that the latest supply tender had gone to an Allahabad company instead of his local firm. Meanwhile, in the pediatric wards, infants lay gasping. Parents wept, doctors panicked, and the machinery of responsibility collapsed under its own weight.

Khan’s account is deeply human; he remembers the sound of parents pleading, the faint wheeze of tiny chests, and his own helpless rage. To read these pages is to encounter not merely a medical crisis but a moral apocalypse. Bureaucracy, hierarchy, and ego—rather than shortage alone—emerge as the true culprits.

From Healer to Scapegoat

By dawn, news of deaths began to spread, and with it, a political storm. The tragedy instantly became a public‑relations nightmare. Yogi Adityanath, who represented Gorakhpur and had once been closely associated with the hospital, visited in fury, demanding to know who leaked the information. When Dr Khan’s name appeared in early reports as the doctor who tried to save the children, admiration online swiftly turned into suspicion. Within days, he was suspended and then jailed.

The memoir lays bare how state machinery manipulates narratives to create scapegoats. Fact‑finding was replaced by fabrication; patriotism by persecution. The government insisted no child had died from oxygen shortage but from encephalitis. Ministers like J. P. Nadda publicly cleared the administration of responsibility, even as photographic and witness evidence contradicted them. As the official line hardened, the media swarmed to find a “culprit,” turning Dr Kafeel into a symbol of negligence.

Khan recounts a surreal silence from colleagues who once praised his dedication. He surrendered to authorities after seeking anticipatory bail, yet police announced he had been caught “while fleeing to Nepal.” His brother Kashif was shot at by unknown gunmen near the high‑security Gorakhnath Temple—an act of intimidation that nearly cost him his life. Their ordeal turned personal suffering into a public parable: truth cannot breathe where power fears exposure.

The Plural World Before the Tragedy

Woven through the book is a counter‑narrative to communal polarization. Khan recalls growing up in a modest, plural environment of Gorakhpur where Hindu and Muslim families celebrated one another’s festivals and shared joys with simplicity. Those recollections of small‑town harmony serve as moral backdrop to the later disillusionment. They remind readers that humanity—not religion—defines ethical duty.

This plural upbringing also shaped Khan’s medical ethos. For him, medicine was an act of compassion, not privilege. Thus, his anguish on seeing children die unnecessarily is grounded less in professional failure than in the violation of that moral covenant between doctor and life itself.

Inside the Jail: A Mirror of the System

The title Aspataal Se Jail Tak (From Hospital to Prison) is not metaphorical—it describes his literal journey from one state institution to another. After his arrest, Khan enters the world of India’s prisons, which he chronicles with almost ethnographic precision. Jails, he observes, reproduce the same hierarchies, corruption, and class arrogance he saw in the hospital.

Inside, money dictates everything: from sleeping space to edible food. Police and guards run an economy of extortion; narcotics and cigarettes move through invisible networks; a prisoner who pays less than demanded, as Khan once did—fifty rupees instead of a hundred—is beaten without consequence. The memoir’s depiction of these details is chilling—not sensational, but matter‑of‑fact, which makes them more disturbing.

Particularly moving are his reflections on loneliness: how, in jail, one learns that the world forgets quickly. Relatives hesitate to visit; visits are bureaucratically rationed; letters, when they arrive, become lifelines of hope. He describes prisoners finding fragments of humanity in festivals celebrated together, and in the collective rhythm of despair and endurance. Yet even in darkness, dignity flickers—he learns to write, to observe, to survive.

Apartheid Behind Bars

Khan terms the internal order of prison “jail apartheid.” There exists a hierarchy of inmates—politicians enjoy special food and bedding; poor prisoners sleep on the floor. Corruption seeps into everything: from visitation passes to medical attention. He narrates how sleepless nights were haunted not only by trauma but by the snoring of dozens of men packed into suffocating barracks, many addicted to psychotropic drugs and charas, supplied with the connivance of police.

What strikes the reader is not only what these details reveal about carceral India but what they imply about the broader state—power itself sustains its ecosystem by dehumanization. The prison becomes a microcosm of governance outside: both rely on fear, control, and selective cruelty.

The Shifting Masks of Power

Once released in 2018, Khan’s ordeal did not cease. His brother remained critically injured, police intimidation persisted, and his reputation remained tainted despite judicial clean chit. When he began publicly rebutting the official narrative about oxygen shortage, the harassment resumed—electricity cut off, surveillance intensified, income dried up. Yet his voice could not be silenced. Crowdfunding through the Ketto platform and citizen solidarity kept his family afloat.

Khan’s sharpest insight appears in his reflection that religion had nothing to do with his scapegoating—he was sacrificed to protect the powerful, not to serve communal animus. “To save himself and other officers,” he writes (p. 202), “Yogi would have made anyone the sacrificial goat.” That phrase captures the heart of the memoir: injustice disguised as governance.

His later imprisonment under preventive laws in 2020–21 for activism during the COVID‑19 pandemic further revealed how dissent is criminalized. When he launched “Doctors on Road,” a volunteer program offering medical aid to disadvantaged regions, and later established the Mission Smile Foundation, he redefined his own trauma into social activism—a reclamation of agency.

Letters, Family, and the Intimacy of Suffering

Among the memoir’s most poignant moments are those involving family. Khan describes his daughter’s tears when she first saw him after his release, his wife’s resilience, and the surreal relief of sleeping at home after months among strangers. But freedom, he confesses, carried scars—nights when nightmares simulated the clanging bars and bruising inspections of jail. Trauma lingers even in comfort.

He also speaks of the “power of letters” exchanged in prison—the handwriting of his daughter or mother that, in that suffocating world, became oxygen of another kind. The transformation of these private correspondences into spiritual lifelines recalls classical prison writings, from Mandela to Faiz. What distinguishes Khan’s account is its rootedness in contemporary Indian experience, where bureaucracy, media, and politics combine to strangle hope.

Anatomy of Denial

Throughout Aspataal Se Jail Tak runs a single, stubborn vein of denial. Dr Khan dissects it layer by layer. The Gorakhpur DM, Principal Secretary (Health), and Director General Medical all knew of the unpaid dues but failed to act; yet the cover‑up machine swiftly assured the public that oxygen was ample and deaths were inevitable. Even the Chief Minister’s remark—“Do you think you’ll become a hero by arranging oxygen cylinders?” (p. 248)—reveals insecurity masquerading as authority.

Rather than introspection, the state responded with islamophobia, misogyny, communalization, and intimidation. What strikes the reader most is not the tragedy’s scale but its ordinariness—how easily cruelty becomes procedure, how quickly accountability becomes “anti‑national.”

The Language of Testimony

The Urdu translation by Imam Mohammad Shoaib and Iram Fatima deserves particular praise. They sustain the immediacy and emotional rhythm of colloquial English without resorting to pathos. The prose carries the authenticity of speech: simple, direct, weighted with pain but never self‑pitying. In a work so politically charged, the translators’ restraint is vital; they let the facts burn through the language rather than sensationalize them.

Pharos Media’s publication itself is an act of courage. Situated within the tradition of testimonial writing, this book enlarges Urdu’s modern landscape by giving institutional critique a visceral voice. It also revives the moral lineage of Manto’s humanitarian realism, reminding us that literature can still speak truth to power.

Aftermath and Redemption

Despite exoneration, Dr Khan was not reinstated in his government job. Other accused officials returned to their posts; he remained indefinitely suspended. That asymmetry crystallizes his theme: innocence cannot redeem an inconvenient truth. Yet, instead of retreating, he turned his energy toward humanitarian work, organizing free medical camps for children, coordinating relief during pandemics, and founding Mission Smile Foundation.

This final turn gives the book its shape of redemption. The same man once vilified as a criminal reemerges as a healer of the poor, expanding his moral radius beyond hospitals or prisons. His activism reclaims citizenship from fear.

Conclusion: Breath as Metaphor

At its deepest level, Aspataal Se Jail Tak is about breath—its absence, its struggle, its sanctity. The dying children, the suffocated truth, and the gasping conscience of a nation form one continuous chain. Dr Kafeel Khan’s story transcends personal suffering; it becomes a mirror in which we glimpse the face of institutional India—cold, hierarchical, and self‑absolving.

Yet the memoir ends not with despair but with defiance. In turning testimony into literature, Khan restores the oxygen of truth to public memory. His words insist that compassion is not weakness, that resistance can coexist with healing, and that conscience, though throttled, can still breathe.

Aspataal Se Jail Tak thus stands as both witness and warning—a chronicle of how easily empathy can be exiled, and how urgently it must return. It is, at once, a lamentation and a manifesto: a reminder that even amid darkness, to speak is to breathe, and to breathe is to live.

(M.H.A.Sikander is Writer-Activist based in Srinagar, Kashmir and can be reached at [email protected])